Ethics are far more than a list of rules.

Ethics are the principles adopted by practitioners

within a field to translate the desire to serve

into the profession’s evolving wisdom

about how best to serve.

~ David Feinstein, PhD and Donna Eden,

Ethics Handbook for Energy Healing Practitioners

The ethics in a professional field of practice are what compel us, motivate us and guide us to offer and conduct our work for the clients we serve with the highest possible levels of integrity and professionalism. The ethics described below are the cornerstones of the Animal Loss and Grief Support Professional Program of Study. Those certified in the program commit to adhere to these ethics and guiding principles, to use them as a foundation of their work and to guide their conduct as they support those who grieve the loss of animal loved ones.

The Code of Ethics and Guiding Principles:

Conduct with Clients

Self Awareness and Development

Confidentiality, Privacy and Informed Consent

Conduct with Others

Four Elements of Effective Facilitation of Healing

Client-Centered, Empathy-Based Approach to Helping

CONDUCT WITH CLIENTS

Sound ethical practice is good counseling practice,

and good counseling practice requires sound ethical practice.

~ Louis A. Gamino, PhD, Ethical Practice in Grief Counseling

1. Holds the welfare and the healing process of the grieving client as their abiding concern, taking precedence over favored healing techniques, tools and philosophies, specialized training, knowledge, and theories. Above all, they strive to do no harm.

2. Recognizes, accepts and acknowledges that grief is indifferent to the species lost, and is exceedingly careful to never condescend, belittle or trivialize, in any way, the death of an animal, the importance of the role an animal may have in a person’s life, or the person’s grief response. Respects and accepts that the following beliefs are held by many people who reach out for grief support when their animals die:

• The life of an animal is as important and significant as the life of a human.

• The death of an animal is as important and significant as the death of a human.

• The grief of those who mourn the loss of beloved animals is as important and significant as the grief of those who mourn the loss of beloved humans.

3. Recognizes and acknowledges that grief, including anticipatory grief, is both an emotional and spiritual experience and that both of these aspects need to be considered, understood and supported when helping those in grief.

• Careful not to encourage clients, directly or indirectly, to ignore or favor either a psychological or spiritual approach to grief healing with comments, strategies, tools or resources that indicate bias toward only one of these aspects having legitimacy or importance. Is comfortable with both of these aspects of grief and grief healing, and is prepared and able to support and acknowledge wherever the client is in regard to these aspects with tools, resources or referrals when appropriate and relevant to the clients’ values.

• Holds a basic understanding of psychological principles of loss, grief and counseling, as well as various spiritual perspectives of loss and grief.

• If practitioners’ original education or strongest orientation about death, loss and grief is psychology based, they take the time to learn more about and are open to metaphysical, religious and other spiritual orientations and beliefs about loss and grief. If practitioners’ original or strongest orientation about death, loss and grief has been metaphysical, religious or otherwise spiritually based, they are open to and take the time to learn psychological principles about loss and grief and basic counseling psychology skills. Commitment is made to support the whole person which acknowledges all aspects of healing grief. Remains open minded and integrative in their approach, and are not reluctant or unwilling to combine love, compassion, psychology and spirituality as appropriate and relevant to the client as they support others.

4. Recognizes that effective grief support is founded in compassion and love and that this cannot come from the ego or from the intellect, but from an open heart. Understands that while having a solid intellectual understanding of loss, grief and healing paradigms is important, during client contact, communication from the heart must come first--exuding compassion, love and empathy to create a genuine healing presence. Our intellectual understanding of loss, grief and healing is an important source of preparation and guidance for practitioners as we support our clients, but if this is unaccompanied and not preceded by compassion and love, our support will be abstract, and likely to be perceived as cold and even useless to those in pain.

5. Recognizes that the role of a grief support practitioner or any healer is a sacred trust and that the responsibility to create a place of safety for the client is a critical one.

• Creates a healing presence by exuding genuine warmth, care, compassion, nurturing, acceptance, respect, non-judgment, encouragement, the expression of empathy and affirmation of the client’s potential for healing and wholeness.

• The spiritual maturity and poise of any helping practitioner, and their ability to create a healing presence for clients, is heightened when they hold the space to help the grieving person or animal find their own unique way to healing--not to push, drag or badger them, however lovingly, into following a path, beliefs, or resources in a way that we think is best.

6. Consistently sets and maintains energetic boundaries as an essential aspect of client contact:

• Energetic Clearing: To protect clients, practitioners commit to a practice of clearing themselves and temporarily putting aside all preconceived ideas, personal values and beliefs about animals, loss, grief and healing while working with clients to prevent possible biases and filters from distorting what we perceive and hear from clients.

• Energetic Protection: To protect themselves and to maintain healthy energetic integrity, practitioners commit to a practice of using techniques for energetic protection to prevent potential overwhelm and compassion fatigue from ongoing exposure to clients’ energy and pain. Energetic protection allows practitioners to be present with intense emotions of others, to feel and to express compassion for them without taking in their pain.

7. Expresses empathy throughout client contact, in an active attempt to understand the clients' feelings, thoughts, stories and experiences from the client’s frame of reference. Listens first, using empathic inquiry to help clients explore their own inner world, and holds back any impulses to immediately “fix” the client’s pain, interpret or analyze. Is exceedingly careful to express adequate levels of empathy before offering any strategies, tools, ideas or healing techniques.

8. Scrupulously refrains from imposing personal values and beliefs.

• Does not use the professional relationship with the bereaved to proselytize own spiritual, religious, or personal beliefs and philosophies.

• Sensitive to the emotional vulnerability, sometimes acute, of grieving clients, which can make them more susceptible than usual to others’ opinions and suggestions, and realizes that it is both disempowering and potentially emotionally harmful to impose one’s own moral views onto clients.

• Steadfast in supporting clients to clarify what is true for them regarding personal and spiritual beliefs and values.

The relationship between clients and helping professionals involves a sacred trust in which clients must feel safe in knowing that helping professionals are there to support them in finding their own way, not to preach or proselytize. To violate this trust by attempting to make clients hold beliefs or take actions based on the practitioner’s values is one of the most egregious and unethical things that anyone in a grief support role can do, even when done unintentionally.

9. Scrupulously refrains from imposing solutions, strategies, tools or healing techniques.

• Offers, rather than imposes, proactively providing grievers a choice about whether they want to learn about or use the tools and techniques that practitioners have available.

• Trusts the wisdom of the client to make such choices on their healing journey, and supports their choices, even when they may choose to not follow an idea, a path or use a tool we believe is best for them.

10. Recognizes that language is powerful and can support or offend. Maintains an awareness of how a practitioner’s choice of words, verbal and written, can infer, even subtly, that a particular belief or view is the “correct” one that grievers should hold. Citing platitudes or inserting personal beliefs into conversations or written materials about death and grief can be inappropriately imposing--even without intention--and can rob or prevent grievers from clarifying or establishing their own beliefs or insult them if stated practitioner beliefs are different from grievers’ beliefs. Examples:

• After they die, our pets are in peace, waiting for us: Implies a Christian, Rainbow Bridge belief that animals do not have a soul journey separate from their human loved ones, but “wait” for their humans to die. This phrasing also implies that reincarnation is not an option, or does not exist, when reincarnation may very well be part of a griever’s belief system.

• There is no death, only a change of worlds: Implies a metaphysical view of death. Unless clients speak in these terms, making it clear that this is their belief, to speak these words to a griever is akin to telling them their animal didn’t really die and infers that perhaps there is no need to grieve.

• Terms for clients' animals: Asks clients what words they use or prefer when referring to their animals, rather than assuming they are comfortable with terms such as bridge babies, pet, fur babies, babies, friend, companion, etc. Understands that it can be very easy to insult a griever when using terms that are not aligned with their values. Until it is clear what words are used and preferred by clients, using terms that are belief system neutral, such as beloved animal or animal loved one are far less likely to insult or upset a griever.

11. Communicates Non-judgment.

• Accepts others' emotional responses to loss and grief, however similar or different their responses

may be from ones own.

• Understands that grieving clients will express a wide range of responses to their loss, from stoic denial to hysterical crying, and accepts and supports all responses. Refrains from labeling any response as normal or not normal.

• Respects the values and spiritual beliefs that clients have about animals, death and the afterlife, whether they are similar to or different from their own values and beliefs, and refrains from proselytizing or attempting to impose one’s spiritual beliefs onto clients or students.

• Respects and maintains a non-judgmental attitude about any services, healing activities or techniques that clients may use to help them with their loss and grief beyond what the practitioner offers the client.

12. Creates and communicates clear logistics policies and boundaries.

It is the responsibility of the practitioner to establish, initiate and maintain clear communication about policies and boundaries. Clear boundaries should be stated verbally and on any websites or print literature to help prevent uncomfortable conflicts (hurt, anger, confusion), which can easily occur when expectations are not clear.

• Fees for services, length of service (for private consultations, group sessions or other modalities such as workshops), and policies regarding when payment is due, in what form, and cancellation policy, etc. should be clearly stated in writing before services are scheduled and provided.

• Time frames of availability to support clients by phone, email, postal mail and/or in person should

be very clear, including when support is available for scheduled sessions or groups, and when it may or

may not be available outside of scheduled sessions or groups. Even when grief support is offered informally,

it is important to be clear with time available for support. It is common for people in crisis to not be as grounded as they may usually be, which may contribute at times to having

unrealistic expectations of 24/7 access to support practitioners. Be clear and honest about time available, and in what form. Resources for alternative support should be provided for clients who

may need support when the practitioner is not available.

• Electronic communication: Boundaries about availability for email, text or social media

communication should be made clear to clients.

• Guidelines or ground rules for support groups should be made clear to all attendees.

• If and when a client refuses work within clearly stated policies or boundaries (i.e., continually

questions, resists or violates them), it is ethically acceptable to decide to not work with the client. In

such circumstances, it is important to explain why it is not constructive to work together.

13. Cognizant of scope of practice .

• Recognizes the limits and boundaries of professional expertise in meeting client needs, and

provides services only within the limits of one's own competence and training.

• Refers clients to other sources of help that are beyond scope of ability/expertise. Has relevant and adequate resources available for referral, which are screened to ensure the improbability that referral sources would trivialize the death of animals or grief from the loss of animals.

• Never diagnoses, unless a licensed psychotherapist or medical doctor.

• Does not represent self as having qualifications beyond one’s training and expertise. Uses appropriate terms to represent one’s work. Graduates of the Animal Loss and Grief Support Professional Program of Study, unless they are licensed psychotherapists, should not represent themselves as a psychotherapist or therapist. The scope of education and training in the Animal Loss and Grief Support Program of Study does not prepare participants to be therapists, but to be grief support practitioners and counselors involving a single focus: short term support for those who are grieving the loss of an animal loved one, vs. longer term, often multi-issue focus of psychotherapy requiring graduate degree training as well as licensing in some U.S. states and other countries.

14. Regarding end-of-life decisions and client reflection upon past decisions:

The sacredness of end-of-life decisions, the transition of death, and the diversity of each person’s spiritual beliefs and decisions must be deeply honored. The grief support practitioner recognizes and acts on the serious responsibility to honor and uphold the right of clients to clarify and embrace their own opinions and beliefs, and to make their own decisions regarding end-of-life issues, unimpeded by a grief support practitioner’s personal values. Proselytizing or, in any way, attempting to impose one’s own personal values and beliefs onto emotionally vulnerable clients at such a time is an egregious ethical violation.

It is the responsibility of grief support practitioners to:

• Help clients clarify what they feel, believe and ultimately decide what is best for their animals in their unique circumstances regarding all decisions about euthanasia or unassisted death.

While practitioners may have important and relevant information (such as medical information

from veterinary professionals or the thoughts and feelings of the animal from a professional animal communicator) or relevant resources to share with clients, these should always

be shared in the context and spirit of supporting clients to make their own decisions. (An exception to this may be when a veterinarian directly and strongly encourages treatment to save a life, reduce pain

and suffering or advises euthanasia to end acute suffering that can no longer be treated).

• Communicate respect for clients’ values and decisions regarding end-of-life choices

regardless of whether the clients‘ values and choices are similar to, or vastly different from, the choices they would

likely make or have made themselves.

• Offer empathic, non-judgmental emotional support to clients as they face and explore

the options to assist their animal in having as peaceful an end-of-life and death experience as possible.

Practitioner support must be steadfastly unconditional as clients make such challenging decisions, or

reflect upon past decisions, regardless of whether a client’s choice is, or was, for an unassisted

death or euthanasia.

15. Serves in an advocacy role to help clients maintain or reclaim their own truth about their relationship with animals, their loss and their grief.

There are individuals in various professions (clergy, mental health professionals, veterinary professionals, animal communicators, healing arts practitioners, authors of books on animals, death and the afterlife, etc.) who strongly assert and impose their opinions onto clients about the limits of how much we should love animals (i.e., not as much as humans); what happens when animals die, how they should die, how we should grieve and for how long; whether animals have souls, and what does and does not happen for animals after death; etc. When such opinions are presented as if they are ultimate truths--whether done so forcefully, gently or charismatically--to emotionally vulnerable, grieving humans, sadly, some of these people begin to question their own beliefs and truth and take on the dogma presented to them.

Without criticizing the source of the dogma, when clients describe feelings such as confusion, unease, doubt, a sense of unworthiness, guilt or anger in response to other professionals telling them that something they believe about animals, how they experience their relationship with animals, or how they’ve handled their grief is somehow wrong, it is the grief practitioner’s job to empower the client to step back to explore, clarify and seek to be at peace with what is true for them--regardless of what any other expert, authority, teacher, etc. declared to them as a universal truth.

The role of a grief support practitioner is to always seek ways to empower the client in their healing process, and is never, ever to tell clients what to believe.

16. Handles termination of relationship with clients with professionalism and sensitivity

If practitioners determine that they are no longer able to capably serve a client, or for any reason is no longer be available to work with a client, they provide appropriate referrals to ensure that the client has continuing care available. It is especially important with longer term clients to ensure that they do not feel abandoned.

In situations where a client cannot or will not work within practitioners’ stated policies or boundaries (i.e., continually resists or violates such policies or boundaries), an ethically acceptable choice may be to decide to no longer work with the client. In such circumstances it is important to constructively and diplomatically explain the reasons for terminating the relationship.

17. Romantic or sexual relationships with clients, students or their significant others is unethical as it could reasonably be expected to undermine and impair the objectivity, perspective or effectiveness of the grief support practitioner, and risks potential exploitation and emotional harm to the client or student.

SELF AWARENESS and DEVELOPMENT

18. Develops the emotional strength and maturity needed to be present with intense pain of others.

Demonstrates a willingness, capacity and ability to tolerate and endure the emotional intensity of client stories, emotional pain and trauma, including descriptions of traumatic accidents, illness and death while remaining calmly and fully present.

Regardless of how intense or extreme the client’s story, emotions or demeanor, practitioners consciously seek to, even in their mind, refrain from:

• Recoiling with a sense of helplessness and sympathy

• Denying or diminishing the pain or trauma of clients as a means to cope with or escape from one’s own painful reaction to it. When we acknowledge the depth of someone else’s pain we need the courage and strength to face our painful reactions to it.

• Feeling compelled to help clients swiftly come to terms with or reconcile their pain because it’s too

uncomfortable to closely observe, be witness to, listen to and be present with ongoing pain.

• Becoming so enmeshed in the client’s pain that energetic protection boundaries are forgotten and the practitioner takes in the client’s pain.

Develops and draws from a well of courage and strength to face and acknowledge the depth of another's pain, as well as one’s own painful reaction to it.

Maintains a healing presence and emotional poise with clients, regardless of the intensity of their stories and emotions, listening and communicating empathy, compassion and love.

Strives to be continually aware of own feelings elicited by client stories and descriptions of loss.

Seeks support for oneself, which may include mentoring, whenever there is any degree of overwhelm, painful feelings, or residual upset from a client story or interaction. Is self-aware enough to discern the difference between upset for the client and upset for own unresolved feelings or issues which may be triggered by a client’s story or pain.

19. Integrates own loss experiences.

• Thoroughly tends to the healing of one’s own losses, including any unresolved issues regarding past losses that may still need healing attention. Seeks help and support as needed.

• Understands that one's own experiences with animal death, loss and grief--even the most profound or transcendant healing experiences--do not equate to a universal truth for all. As practitioners, realize that own experiences provide an important, personal baseline of understanding and shared experiences with clients. However, this does not include the assumption that what helped us will help everyone. Understands that it is vitally important to refrain from making generalizations to others about animal death, loss and grief created from one's own personal experiences.

20. Strives for intimate self-awareness.

• Continually explores and attempts to understand own reactions to and experiences with death, loss, grief and healing, and to clarifies one’s values and beliefs about life after death.

• Recognizes that on-going attempts for honest, in-depth, accurate self-awareness facilitates personal learning, healing and growth. Also recognizes that it heightens awareness of how personal experiences, values and beliefs impact one’s thinking and professional work in grief support. Is conscientious about self awareness to prevent unconscious generalizations based on personal experiences and inappropriate imposing of personal beliefs.

21. Commits to continual professional education, learning and growth.

Diligently attempts to increase knowledge and enhance skills in the field of animal loss and grief support through classes, reading, mentoring, conferences, etc. Continuing education is life long.

22. Seeks mentoring help from teachers or more senior colleagues

Throughout career seeks guidance, feedback and counsel for difficult cases, challenging situations, puzzling client issues and ethical dilemmas from mentors, senior colleagues or trusted, respected peers in the case of senior, long-experienced practitioners.

Initiates such coaching and support sessions in an effort to continue to integrate real-world learning with the perspective of those with more experience to both enhance their own career satisfaction and to provide the highest level of competent and ethical service to clients.

CONFIDENTIALITY, PRIVACY AND INFORMED CONSENT

23. Respects privacy and confidentiality of client information

• Regardless of the specific role of a grief support practitioner, all information about and from clients, including

name, contact information, and information about client’s loss and/or consultation/case details must remain private and confidential.

• Informs clients of confidentiality policy verbally and in writing.

• Safeguards all files and written information about clients for privacy; any disposed files are shredded.

• When referring to client stories and cases in teaching, presentations, writing, or in mentoring and coaching sessions, does so only when receiving client permission and or completely disguises the information to maintain client privacy and confidentiality.

• Does not discuss clients by name or in any recognizable manner on websites, in social media, with peers, in the community, with friends, family, or anyone else.

• Regarding placement of client information in practitioner database: asks permission before entering client information in a newsletter list; never sells or gives away client contact information; if sending mass emails, client email addresses are kept confidential by entering them in the “bcc” [blind carbon copy] where recipients will not be able to view the addresses.

• A deceased person’s right to confidentiality does not expire at death.

Exceptions to Confidentiality (from Association of Death Education and Counseling*)

1. Client authorized release of information

2. Danger to self

3. Danger to others

4. Neglect or abuse of children or vulnerable adults [or animals--addition by Teresa Wagner]

5. Complaints or litigation against counselor

6. Litigation claiming pain and suffering

7. Court-ordered or statutory requirements to disclose

8. Requirements of third-party payers

24. Solicits client permission and informed consent

.

• Clarifies services, approach and processes to be used during a session. Before consultations/services

are scheduled and provided, practitioners inform clients with a full and complete description of how

they work, any particular techniques they may use, a range of reactions clients might expect from the

work, what results may occur or not occur from the work and how the practitioner will support the client.

• Obtains permission before using specific techniques. Regarding specialized techniques or healing modalities in which the grief support practitioner has training and expertise, they must be used only

with the permission of the client and should be offered only when it seems apparent that they fit the needs and goals of the client.

• If the grief support practitioner is also a professional animal communicator, or has telepathic animal

communication abilities, the practitioner refrains from connecting telepathically with the client’s animal unless and until the client specifically requests and or grants permission for this service.

Having a conversation with a client’s animal, including after death, without the client’s request and/or permission is an egregious violation of client expectation of privacy and professional boundaries.

• Audio or video recording: practitioners may not record sessions with clients without informed consent

which must be in writing.

From the Association of Death Education and Counseling*:

Informed consent is based on the ethical principle of autonomy, respecting client’s right to self- determination. Repetitive interplay of permission-seeking by counselor and permission-granting by client that honors client autonomy at each juncture in the therapeutic process.

Two consensual elements:

• Full disclosure by practitioner of pertinent information client needs to make a reasoned decision

• Free choice by the client to proceed, without pressure or coercion

Consent is ongoing and revisited throughout the cycle of care, not a one-time event ratified by signing forms or by saying yes one time to receiving a healing modality.

* http://www.adec.org/adec/Main/Discover_ADEC/Code_of_Ethics/ADEC_Main/Discover-ADEC/Code_of_Ethics.aspx?hkey=6ef825fd-775c-4ae8-9090-8ed3ca2c5cd1#Served

25. Maintains a respectful, professional and considerate demeanor and behavior in relationships with clients, students, mentors, professional associates and peers at all times, including when a conflict or difference of opinion exists.

26. Regarding the use of others’ work:

• Respects the energy and efforts of others that was used to create proprietary work by never plagiarizing or in any way using or representing the intellectual property of others as one’s

own.

• Requests permission before using copyrighted information for any purpose.

• Familiarizes oneself with, and abides by, copyright law before sharing information (including text, graphics and photographs) that was created by others in their books, websites, class handouts, blogs, etc. See US Copyright Law, Fair Use.

• Always credits the author of any work cited on one's own website, blog, social media pages, brochures, workshop materials, etc. including author name, name of publication, and website where available.

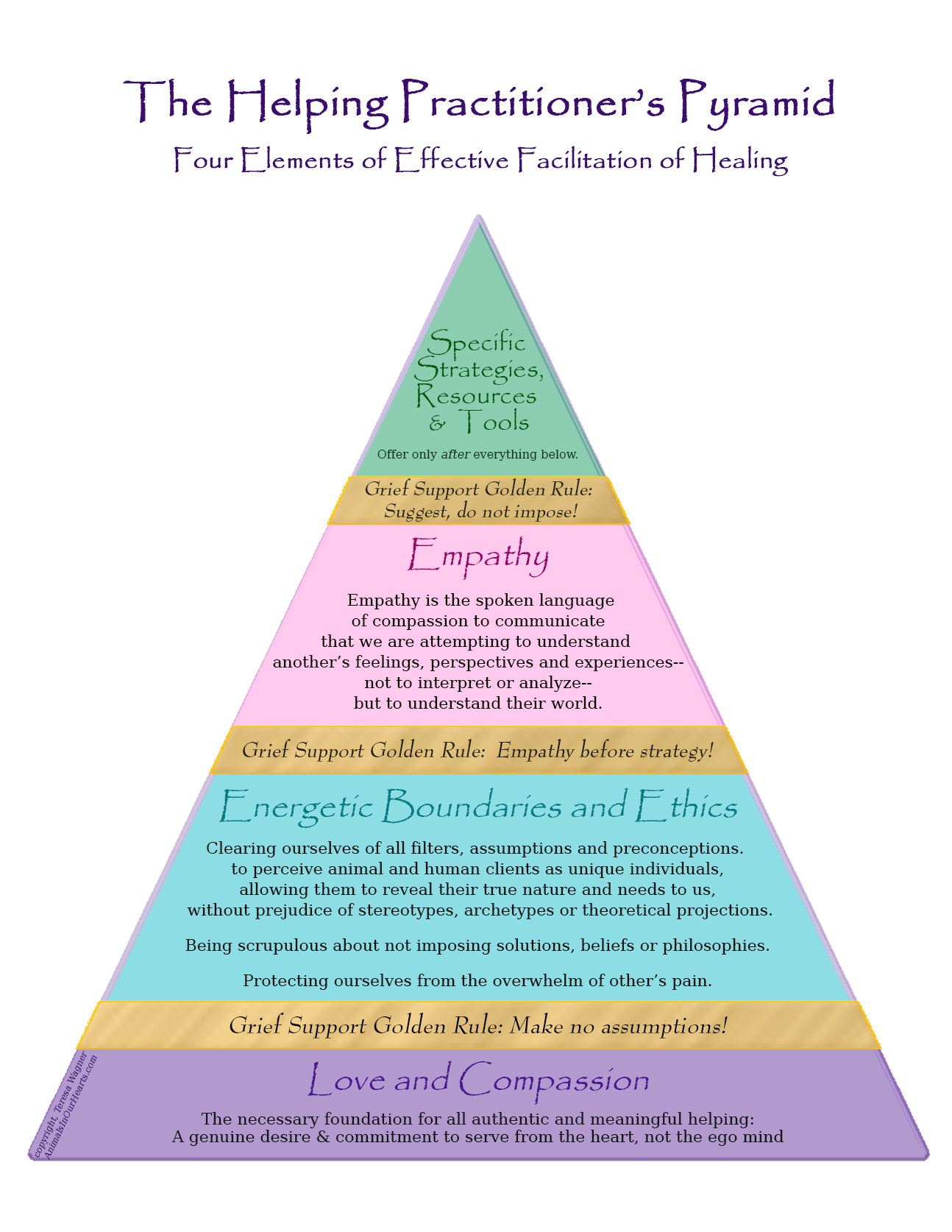

The Four Elements of Effective Facilitation of Healing

More about the Four Elements of Effective Facilitation of Healing

People often begin offering healing arts and grief support work greatly motivated by love, compassion and a genuine desire to serve. While this is a profoundly important foundation, many bypass the need for energetic boundaries, ethics and empathy to delivering specific healing tools and philosophies without first checking in with the client to learn their real needs. Being unaware of the value and role of energetic boundaries, the ethics that are central to the helping professions, and the fundamental, powerful role of empathy in helping relationships and the skills needed to express it effectively can greatly undermine the effectiveness of the helper and the help given.

Let’s take a look at what can happen when practitioners move immediately from loving compassion to offering strategies and tools to clients without energetic boundaries and empathy.

Without awareness and scrupulous attention to energetic boundaries and ethics,

we are at risk of:

• Projecting our own beliefs, ideas and values onto clients--even unconsciously--and becoming more of an

evangelist who is imposing views rather than being a skilled, effective helper empowering others to heal.

• Filtering our view of our clients’ situations (and thoughts and feelings) through the lens of our personal beliefs and paradigms, preventing us from seeing the client’s perspective because we are viewing/analyzing their situation from only our perspective.

• Burning out if we do not have adequate understanding of or don’t practice taking precautions regarding not taking in the pain and energy of others, and not setting boundaries regarding how we work, when we work and with whom we work.

Without empathy, the strategies, tools and ideas we offer may be:

• Premature if we haven’t taken the time to ask for and listen to our client’s story, thoughts and feelings before suggesting or implementing modalities and tools.

• Irrelevant if not a match to the client’s needs (which happens easily when we don’t ask for and listen to their needs first).

• Inappropriate if not a match to the client’s needs, which we can’t know for sure until we’ve heard and understood their thoughts, feelings and stories.

• Unwanted or a waste of the client’s time, if not matched to their needs which we cannot understand fully without first asking for and thoroughly listening to their stories, thoughts and feelings.

• Irritating to any client who is aware that they have not been listened to and their needs not taken into account before practitioners launch into what they “know” will help them. This can anger those clients with ample strength and self esteem to be offended.

Making premature, irrelevant, inappropriate or unwanted suggestions or comments can retard the healing of vulnerable clients who may become dependent on our views as we impose on them the way we believe they must heal. This is not the job of a helper/healer. It is to empower clients to find and determine their own way with great love, with healthy boundaries, with tremendous empathy and with skill.

Empathy is the bridge to offering strategies and ideas to clients.

Without it, we are leaping blind, guessing (or not caring) what our clients need.

Our expertise in the helping fields in which we have been trained can be priceless in helping others through challenging times. It can also be worthless if our delivery lacks empathy, energetic boundaries and ethics. But when we combine all four elements--love & compassion, energetic boundaries, empathy and the tools in which we’ve been trained--the support we offer others is powerfully whole, relevant and highly empowering to the clients we want to help.